Return to North Glen

or Reading List

or Credo

"It

doesn't take an expert in the manipulation of

statistics to

understand that the survival of the entire

human species depends

on a sustainable relationship to

the local expression of the

processes of the biosphere."

-- Freeman House, Totem Salmon,

19995

Self,

Soul & Community

By Ed Iglehart

Three words with

strong emotional content; evocative words, provocative words, much

used, abused, confused, de-fused, often mis-construed, sometimes

downright rude. Three words linked as aspects of a larger whole?

Might we say "Spirit," and where might that get us?

"We

have been repeatedly warned that we cannot know where we wish to go

if we do not know where we have been. And so let us start by

remembering a little

history."

--

Wendell Berry, Farming and the Global Economy, 1995

But

how can we know where we have been without knowing where we are? Best

to start at the end and work backwards? A community's spirit must be

embodied in the physical realities and cultural history - the

biophysical and successional ecology - of a place. I cannot imagine a

community without a substrate - rock, atmosphere, liquid water - the

so-called non-living (inorganic) materials, and it is difficult to

imagine community without life, and therefore history. Life would

seem to be the process by which the inorganic hitch-hikes and surfs,

riding and elaborating the complex dissipation of energy and increase

of entropy - fire. So we arrive at the classical four elements.

But

what about scale? How big a place? Gaia's a place, and certainly a

community, but a rather large subject for the present purposes. So

perhaps that part of Scotland politically delimited as Dumfries &

Galloway? Still far too big. How about the Stewartry of

Kirkcudbright, an ancient county between the rivers Cree and Nith and

bordering Ayrshire along the watershed? Why do we start with the big

and subdivide? Is the larger more important? Perhaps we can start

with the small and work outwards, but how small? Maybe quarks is a

bit extreme, and though I know they are there, the bacteria in my gut

are an abstraction; all I can visualise is microscope slides, so

perhaps self is as good a beginning as any.

But although I'm a

community constructed of differentiated cells, each populated by

mitochondria and other passengers, navigators, engineers and

distribution systems, the whole multi-cellular construct itself

co-inhabited by countless microbes, all engaged in the process called

life, I should still feel lonely without other units similar to

myself. And, to avoid descent into cannibalism, it will be necessary

to recognise community with other large and small non-human

life-forms outwith the arbitrary but convenient boundary of my

epidermis. And there's the 'substrate' as well, the geophysical

context within which we go about this living: rock, water and air.

It's still pretty hard to find an appropriate boundary.

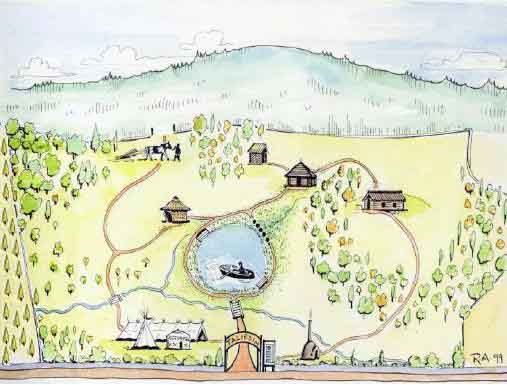

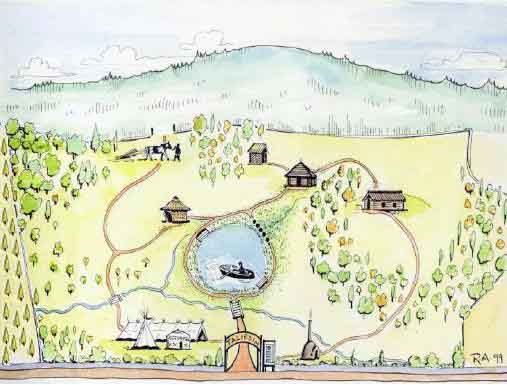

I live

in the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright,1

near the lower end of the valley of the Urr Water. North Glen is the

core of a small farm that is half woodland. Starting from my back

door, I could walk for days and rarely leave the woods except to

cross the roads. Though the Stewartry is known as a farming county,

one third of it is wooded. From the hillside behind my house I can

see thousands of acres of trees in the Stewartry and neighbouring

Dumfriesshire. Sadly, the majority of these are fast growing conifers

whose genetic origin is overseas and whose destination (via flush

toilet) is the sea.

There are, however, many small and a few

larger remnants of semi-wild, semi-native woodland, often including

broadleaved species from afar. Many of these trees are standing on

steep slopes of the river and creek valleys that were cleared and

ploughed at intervals from the early years of settlement until about

the time of World War II. These are rich woodlands nevertheless. The

soil, though not so deep as it once was, is healing from agricultural

abuse and, because of the forest cover, is increasing in fertility.

Some has never been ploughed or otherwise 'improved'. The plant

communities consist of a few Scots pines (whose nativity is in doubt,

being absent from the pollen record) and a great diversity of

hardwoods, shrubs, and wildflowers.

|

|

The

history of these now-forested slopes over the centuries of

human occupation can be characterised as a cyclic alternation of

abuse and neglect. Their best hope, so far, has been

neglect-though even neglect has usually involved their degradation

by livestock grazing. So far, almost nobody has tried to figure

out or has even wondered what might be the best use and the best

care for such places. Often the trees have been regarded merely as

the occupants of 'waste ground', which, because of the steepness

of the terrain, has been unavailable for better use. Much of the

relatively recent conifer forest has been a last resort use after

centuries of overgrazing. Ploughing vertically to improve drainage

prior to planting has increased acidification, erosion, &

siltation in the watercourses and destruction of gravel beds with

disruptive effects on aquatic life, from the bottom of the food

chain (at the top) to salmonids, wildfowl and others at the top of

the food chain (downriver!)

From

the watersheds above Loch Urr to the waterfoot where it meets

the open Solway Firth, the Urr Water is no more than 40 kilometres

as the crow flies. The river and its tributaries traverse rather

more, however. Most of the relatively narrow valley system is a

patchwork of fields, conifer plantations and areas of mixed

woodland, many of ancient and semi-natural character. Over

the watershed to the east lies the Nith Valley and Dumfriesshire,

to the west is the Ken/Dee catchment. The "Paddy Line,"

a rail link which ran from Carlisle to Stranraer, stopping at

Dalbeattie was closed and removed in the '60s. The only major

motor route crossing the valley is the A75 Euroroute, and there

has been very little development in the modern sense. Below the

upper tidal limit the area has a sea-faring heritage, as local

gravestones testify, and it's probable the first humans arrived by

sea, as did Christianity later to nearby Whithorn.

Auchencairn

Bay is divided from the foot of the Urr estuary by Almorness

peninsula, and interacts with it daily as the tides ebb and flow.

At the head of the bay Screel and Bengairn rise to 1200 feet with

large areas of conifer forest, heather, waterfalls and

semi-natural areas, including Taliesin, an area of old meadow with

mixed woodland regeneration. Red squirrels live throughout the

valley, as do many other wildlife folk. A relatively low divide

separates the Urr from the nearby Dee catchment, and a canal was

once planned between Palnackie and Castle Douglas, using only four

locks. It remained undug due to the advent of the railway, and the

route is now bordered throughout much of its length by woodland of

many types.

|

The

largest town is Dalbeattie, six thousand folk with around three

thousand acres of public forest as a backyard. Another couple

thousand people are distributed downriver between the forest's flank

and the river's eastern margins. The port at Dalbeattie which once

exported granite for the Thames Embankment, is now largely disused;

the only remaining quarry crushes the granite for roadmetal. Kippford

is a small sailing resort, and at Rockcliffe there are beaches. There

are perhaps another two thousand folk scattered among the valley's

farms, hamlets and villages. Except for the Highlands, the Stewartry

is the least densely populated part of Scotland.

On the

west bank is Buittle, an ancient seat of power and home of

Devorguilla, wife to John Balliol, whose heart she buried at

Sweetheart Abbey by the Nith. Downriver a couple of miles,

Palnackie's port serves occasional cockle boats and some recreational

use. Further down, the west bank consists of Almorness peninsula

stretching four miles beyond Palnackie, with only three families in

occupation, including ourselves. From The Anchor, in Kippford it's

impossible to see any buildings on our side, and my neighbour Angus

and I speculate on mounting a wildman raid across the river at low

tide, painted with woad, yelling and waving spears. We'll shake up

the tourists and swank sailors and accept tribute in pints.

|

|

On still

fullmoon nights, the spring tide is highest around midnight,

and the double bend below the farm becomes a large lake with

hundreds, if not thousands of birds; ducks, waders, allsorts.

Overnight guests sometimes complain the birds keep them awake,

what with meeting and greeting all their aunts & uncles

assembled to await the tide's retreat. On one such night I walked

down through the wood to where the canoes are stashed (eight miles

to Kippford's two pubs by tarmac & fossil, a few hundred yards

by water & metabolic), and launched myself. There was little

need to paddle, as I drifted upriver on the rising tide.

|

When

I did get up a bit of speed, there was a phosphorescent double mini

bow wave. I tried being very quiet to coast in among a flock of ducks

I could just make out. As I got almost near enough to see them

properly, they fluttered off a few dozen yards. After thus failing

several times, I relaxed and just drifted, disappointed. At slack

water I found myself looking up at North Glen on its bluff. I could

see Tom's campfire in the treetops and hear the voices of his

companions - quite a party. I opened a can and had a smoke, just

watching and listening.

The tide turned and took me back down

to my launching point, and climbing out of the canoe, I fell in the

river . Walked back up through the woods wet and happy. It was

several days before I forgave the ducks. "Typical human! We're

out here every bloody night, fair or foul, and (once in a blue moon)

some creep thinks we won't notice him crashing about on a millpond.

Huh! I thought you said they were supposed to be clever!"

Forestry,

after farming, is the second largest land use in the Stewartry, but a

meagre provider of the promised employment. That which is generated

too often feeds bank balances in distant cities. Large forest

holdings are more general than small, owners, if human, rarely

visiting and even less frequently alighting from their off-road

vehicles. To be fair, the relatively large holdings of the Forestry

Commission offer the most visited 'attractions' to the small, but

economically important tourist trade. Management policy and decisions

on these 'publicly-owned' forests are made in distant, carpeted,

double-glazed offices by people who are too busy in most cases to

ever set foot in them. For these people the forests consist of lines

drawn on paper and pages of statistics, or landscape simulations on

computer screens. The same is true of most other agencies of the

centre, whether focussed on "things" or people. The scale

is wrong.

Our larger modern cultural matrix is severely

dis-empowered through centuries of such increasingly centralised and

abstracted authority. I reckon the commonest pronoun in use is third

person plural. The 'improvements' of communications in the broadest

sense - roads, motor transport, telecommunications, etc. reach even

to Palnackie (pop: ~300); now there's an evening rush hour as local

residents return from work, mostly one per auto-mobile.

Decades

ago,

We mostly walked to work,

Side by side with friends &

neighbours

We worked and walked together,

Ate, drank, fought,

loved & raised the young together,

Grew old, returned to local

soil together.

Now it's better,

We have improved

communications,

Roads & hyperspace, phones, TV, &

cyberspace,

Keep us 'in touch' with world events,

Our glazed &

insulated capsules keep us safe and warm,

And free from nosy,

noisy, noisome neighbours.

This new species,

Encapsulated

Humanity

In a migrating herd, following its beaten track,

With

unconscious choreography,

The ribbon of steel and red light

Snakes

slowly cityward.

The big cat waits,

Sporting

fluorescent stripe,

And purring sinew of steel.

From his

elevated post,

He watches with laser eye,

Choosing only the

swiftest as his prey.

--

"Homo Encapsulata" 1996, Ed Iglehart

Community

was easier to identify when, not so long ago, everyone walked to

work. It was the folk we walked with, worked with, came home with,

drank with, argued with, - in short, those with whom we shared life

and locality. Now there is a community at 'work' which is drawn from

a 40 mile radius or more, the scene of career strategems,

flirtations, betrayals, etc., just as before, but separated from

'home' by some sort of hyperspace journey morning and evening. Mixing

with our fellows on the return journey leaves us unfit company for

anything but a TV set. This provides what every responsible citizen

must have: a complete update on the affairs of the entire global

'community', its wars, inhumanities, & disasters, all thankfully

sufficiently distant to be out of reach, but for a conscience-easing

credit card donation by toll-free number. When a neighbour dies, we

wonder who to notify (if we notice!)

For many, 'home' has

become a territory whose size and degree of fortification is in

direct relation to financial status, proof against a hostile

environment. It's an irony of our time that we who think of ourselves

as the age of emerging environmental awareness are also the most

accomplished at isolating ourselves mentally, physically, and

spiritually. Out of a thousand footsteps it is unlikely that as many

as ten fall on un-prepared surfaces. We rarely know the phases of the

moon, see wildlife mostly on the cathode ray tube, and scenery

through the windscreen. Darkness has been banished by electricity so

that the only real difference between night and day is the television

schedules. The use of the logically meaningless word 'un-natural',

invariably in the pejorative, speaks volumes, for it is used to mean

'human', and such self-hatred cannot be healthy.

But it's

easy to be negative, and while our local communities share much of

this Euro-American malaise, we are better off than many, being

blessed with backwater status (mixed blessing!). Palnackie is a

seaport, but it is a long time since it was really on the way to

anywhere. Sixty years ago the school was overflowing with

farmworkers' and woodcutters' kids; horsedrawn transport served three

sawmills down by the harbour and other haulage businesses, a legacy

from the coastal trade, and horses still towed boats upriver.

Although the last coaster was in '77, farming manpower has

shrivelled, and the best trees were gone by the fifties, we still

have a large haulage business, a joinery and building firm (The main

partner was the first apprentice (of sorts) at North Glen and then

travelled to the antipodes, worked here and there and came home to

marry his schoolmate), a scrapyard and skip maker & hirer

(Shavins, a sawmiller's son), a pub, shop/cafe, nursing home (yes,

we're quite modern in some ways!), caravan site just outside the

village, and down river (but up a hill) there's a glass workshop. We

have a double handful of fine core families and a two-teacher school,

the heart and soul (and future!) of the community.

There are

still many folk in Palnackie whose grandparents were born within

walking distance. Even so, of the village and surrounding community,

only a few walk more than a half mile beyond the houses. The

regeneration of communities is a process which may occupy us for a

large part of the next millennium, and, as most who have considered

these things agree, it cannot be done from without. Few, if any, of

us know fully what community really is/was; all consider its demise

undesirable. I now suspect that 'improved communications' may not be

the unquestioned good we once believed.

In our rural

communities we are said to suffer from peripherality (c.f.

'backwater'). We are at a distance from much of mainstream culture,

and much of the effort of those who would help is spent in devising

ways to strengthen the connections to the dominant and largely urban

culture which lies behind the paradigm of globalisation. Those who

visit our area usually comment on the slower pace of life, the

beautiful countryside, narrow winding roads, the open, friendly

character of the folk. Despite chronic unemployment and shifting

demography, rural society here is still relatively whole; in

conversation with anyone for the first time it's usual to quickly

discover friends, aquaintances and favourite places in common. It's

not that everyone knows everyone else, but everyone knows pretty well

who everyone is. The postie, not being allowed to collect unstamped

mail, helps himself from the till, buys stamps in the village, and I

get change the next day. A member of SCW,2

he often lingers (We're the second last stop of the day. I know his

father, A JP and onetime provost of Castle Douglas). Such a culture

has little scope for dishonesty, and there is very little crime.

A

constable distributing notice of a meeting has to stop and chat a

while (he was in the village youth club when I was leader) The police

came to the village hall with their Neighbourhood Watch roadshow; the

hall was full as the whole community had been leafleted by hand. They

showed a video of streets and talked about break-ins, car theft,

vandalism and such, and asked if we had any questions.

Silence.

Then John Kirk says, "Well, I was born a quarter mile from here

and I've lived all my life in Palnackie. A lot of folk here can say

the same. I can't remember anybody's house ever getting

burglarised."

"Oh yes. There was Jenny's house got

broken into!"

"Aye, but that was the Post Office. And

it was thirty year ago!"

It turned out that the

complaint which brought the roadshow to town was kids hanging out at

the cross, chatting with friends, and occasionally a car would speed

off. It's been a meeting place since before there were cars. The

occupants of the house on the corner felt it was a nuisance. We got

Neighbourhood Watch signs and the kids hang out there a bit less.

When I came here first, I had never lived in one place longer

than six years, and in most it had been far less. From the foregoing

paragraphs it will be clear that I have developed a strong attachment

to my adopted locality, its air, water, & stone, its plants,

animals and its people (and ducks!). It's a great privilege to live a

long time in one place, especially such a place as this. The

detachment from places and their histories which modern living and

its migrations and commutings engenders is a sickness of the soul.

That many sufferers are unaware of this as a pathology is because it

is so normal.

In my three decades here, there have been no

less than seven successive District Forest Officers (DFOs)

responsible for the 150,000 acres of Forestry Commission woods in the

Stewartry. The Dalbeattie Town Wood merges into the rest of the

Dalbeattie Forest. There are miles of footways & cycle routes

among lochs and hills with areas of forestry in all stages. There's a

large user base comprising interests from deep ecology to

dog-walking, and the Dalbeattie Forest Community Partnership is

developing a growing participation in all aspects of management.

Although physically isolated to some degree by the river, I'm an

active supporter of these developments, both personally and through

Southwest Community Woodlands Trust (SCWT).2,3

Adjoining North Glen and opposite Kippford lies Tornat Wood,4

where many of these lines were written. For at least ten years I have

tried to encourage the Forestry Commission to designate it as a

community wood for Palnackie, badgering a succession of DFOs. At

first, when the opportunity arose, I dragged the man through bracken

& briar and got verbal acceptance that amenity should be the

dominant value for the wood. Later, when it was in preparation for

sale, our community woodland group were in position to buy it, but

Scottish Natural Heritage wouldn't make the necessary binding

recommendation (SCWT was a new group with no "track record"),

and the best we could get was its removal from the disposals list. We

then got verbal agreement from the new DFO that it should be managed

in partnership with the community council, but progress towards

formal partnership is slow (no bad thing?). Local young folk (with

some encouragement) have begun to use their own initiative, have

cleared and signposted paths and talk of building a bird hide which

may do duty as a bothy at times.

At the top of Tornat on a

sunny afternoon in a light northeasterly breeze, seagulls and

buzzards cry and circle below high jets singlefiling southwards.

Across the Solway, the hazy mountains of Cumbria taper down to St

Bees Head. Just around the headland, out of sight and long ago, the

Queen opened Calder Hall. Britain's nuclear electricity was going to

be so cheap it wouldn't need to be metered. The adjoining plutonium

recovery facility has been re-named frequently, reflecting its habit

of thinking (and lying) globally while acting locally (and shamefully

carelessly) - Seascale, Windscale, Sellafield, what next? Never mind,

for the moment, it's downwind...and as I muse, company arrives. He

retired from North London to Gelston (4 miles away) eight years ago,

and we swap favourite walks, talk mountains, lochs and waterfalls and

the need to get young folk outdoors. As he is setting off, a father

and daughter arrive. He's from East Kilbride, now Dalbeattie, a

retired aircraft engineer (Merlin engines), widowed last September.

Daughter is cabin crew with BA out of Brighton; grandkids in Dumfries

and Arisaig (spoiled by streetlights). He often used to walk in the

dark several miles through the forest from Dalbeattie for a pint at

the Clonyard. When folk asked "Aren't you afraid?" he

replied, "of what?" They have left the car at the port in

Palnackie ("It makes us walk!"), and like my earlier

visitor, it's the first time they're come this way, thanks to the

kids' pathwork and signs - wonderful!

The sun is warm and

from the opposite quarter to the wind. I settle down in the lee of a

tussocky outcrop and enjoy the vista of bracken, down and brown, with

green emerging on the gametrails (just). A young larch in the middle

of the bracken has made a complete corkscrew turn, but has now sorted

out vertical with its leader; on the east, white birches and green

pines edge the meadow, and over the steeper western edge the tops of

oak, beech and sycamore are still bare of leaves. In dead centre sits

Rough Island, its causeway and the flats clear, but the river's

channel is nearly full and will soon overflow as the tide rises.

Further down the estuary the channel swings in close to Gibbs Hole

and its wood, mixed and full of bluebells. The Granite outcrops still

have iron anchor rings for seagoing sailing ships. A path, formerly a

cart track, can be followed from the anchorage through mature

broadleaf woods along the base of the peninsula to South Glen, and

Palnackie passing Tornat and North Glen. This served ships unable to

wait for larger tides, or with small amounts of cargo to discharge.

Above the broadleaves, Castle Hill has been clear felled

(and, sadly, replanted in spruce) providing a magnificent 360 degree

viewpoint until the new trees get away. I could walk to Almorness

House, beating the tide across the mudflats, and thence to the

hilltop and home the long way, but it's too nice here in the sunshine

and out of the breeze. A falcon flies from right to left, low grey

and smallish (a Hobby?) and down through the pines. I think he saw me

lying here, still but not camouflaged. Cock pheasants crow and fly

across; the hens will be hidden in cover, sitting on eggs.

The

settlements and windmills are visible in the distance on the English

side. Across the river at Kippford, there are boats on the mud and

larches just greening among the evergreen slopes above the village.

The Muckle Lands are a high bluff of bracken and stone crossed by the

new power line, which marches from Dalbeattie straight through the

National Scenic Area, where planners won't easily allow a doghouse.

The power grid apparently has eminent domain, and Kippford now has

streetlights, over the objections of most residents. Scenery

apparently only matters in the daytime.

The sun is trying to

go down, so I set off down the meadow and swing around the west face

through beech, sycamore larch & oak. The ground is covered with

long green bluebell leaves and moss - very little grass. The

buzzard's nest is quiet for the present, as is the rookery, and the

dogs explore rabbit holes and chase squirrel scents. As I follow the

contour (musn't lose height!), a bright flash of light is reflected

from one of Angus' ditches as I pass through alignment with the

slanting sunlight. It cuts the alluvium parallel to the shoreline

some 300m away, efficiently flowing between twin, straight fencelines

enclosing bare banks. A horse is grazing and lambs are calling to

their mothers. The farmhouse is quiet.

Further along, dropping

out of the wood and onto the track, I stop to lean on the Glen Gate,

where Palnackie folk would come to look out to Gibbs Hole to see what

ships were tied up. When Annabel was young, we used to pause here,

and she would go up into the wood to a pretend kitchen in a tumble of

boulders, and prepare an imaginary cup of tea for us to sip while we

leaned on the gate and looked out to sea. The pond and channel here

supplied water power for a horse-drawn itinerant threshing mill, and

perhaps at other times, but was insufficient for continuous use.

I

have trees on other folks' land, and not all of them know. It's

natural regeneration, phantom treeplanting. The ash people have

learned that survival is aided by sprouting right next to a young

hawthorn, and this successful pairing is common around here. Noting

this, I have evolved a mixed relationship with the bramble people and

others of their ilk. In places on behalf of the bluebell folk and

others, I've made war on them, and in others I've planted native

trees among them (protected by their hostile nature from cattle and

sheep, and from rabbits by plastic) which will eventually form

woodland canopy from Tornat halfway to Palnackie, and this may be

extended to the village and beyond towards Kirkennan and Munches.

Both of these relatively small estates are rehabilitating and

extending native woodland bordering the river. Their larger woods,

actively managed for two centuries or more, contain many fine trees,

native and exotic.

Over the rise and approaching home I visit

one of my favourite trees. Part of the hedge along the roadside, its

roots are under the road, but one branch escaped the hedge-mangling

flail by extending itself horizontally until out of reach and has

since grown to a goodsized trunk, while still keeping up the

hedge-disguise on its flank. I've sometimes pointed it out to

children as "the tree that got away," and speculated that

someday it will be blown over and lift a great hole in the road. I

imagine them with their own children: "Do you remember old Ed?

He used to say this would happen."

Tom Niven, whose

father (also Tom) owns the fields next to the village, proposed

reinstating the towpath from the port at Palnackie downriver to

Tornat as a "millennium trail." Angus, who owns the rest of

the riverside, was in full agreement, but after much enthusiasm and

support from officials and residents, the project had to be abandoned

(postponed?) because the owner of the first fifty meters denies the

right of way. There is little doubt that recourse to law would

confirm a right, but patient counsel prevailed. In the meantime, Tom

& Angus have contributed a wee bit of steep land where their

fields adjoin as a millennium viewpoint beside the Glen Road. It has

been levelled and dyked; bulbs and a couple of trees planted (The

hedge already has two good oaks emerging, thanks to ribbons tied to

confuse the hedge-mangler).3

Sam

Thornely has gotten a millennium award to make furniture for the

viewpoint, for which he's set up a greenwood workspace in a tipi at

North Glen. He's involving the Palnackie schoolchildren (and me),

helping them establish a tree nursery at the school, using seedlings

they collected from the wood next to the school. The wood for the

furniture is mostly windblown oak from Kirkennan wood, and a couple

of weeks ago, the 'big room' kids. teacher and a couple of parents

went up into the wood to see Sam free a butt from its rootplate and

cleave it in half. Boggy, (a traveller) and Pinky (his horse) then

pulled the halves down to the road.

As we walked up to the

location, two wee girls updated me on their progress in reading the

Lord of the Rings in class. I saw the first swallow today,3

and a few flower spikes on the bluebells. After the holidays (but

before the bracken is up) we'll lead an expedition to Tornat to see

the bluebells and other things. It's a wonderful place for dens.

"To

put the bounty and the health of our land, our only commonwealth,

into the hands of people who do not live on it and share its fate

will always be an error. For whatever determines the fortune of the

land determines also the fortune of the people. If... history...

teaches anything, it teaches that." -- Wendell Berry, Another

Turn of the Crank, 1995

Ed

Iglehart 15/04/2000

Notes

1. To avoid (or admit)

the charge of plagiarism, I must be explicit. The form and structure

of these three paragraphs are directly derived from the opening

paragraphs used by Wendell Berry in his essay, "Conserving

Forest Communities," in Another Turn of the Crank (1995). They

formed the opening of a letter I wrote to Berry, a few years ago,

asking if it would be ok to copy bits of his essays (or even whole

essays) for distribution amongst fellow local activists. He replied

in pencil, saying it would indeed be nice to chat, should we be in

each other's vicinity, a friendly greeting, but no answer to the

request. In the opening to another, earlier essay, he writes:

"In this

Christmassy atmosphere, an essayist must be aware of the danger of

becoming just one more in this mob of drummers. He (as a matter of

syntactical convenience, I am speaking only of men essayists) had

better understand with some care what it is that he has to sell, what

he has to give away, and certainly also what he may have that nobody

else will want.

I do have an interest in this book, which is for

sale. (If you have bought it, dear reader, I thank you. If you have

borrowed it, I honor your frugality. If you have stolen it, may it

add to your confusion.) Most of the sale price pays the publisher for

paper, ink, and other materials, for editorial advice, copyediting,

design, advertising (I hope), and marketing. I get between 10 and 15

percent (depending on sales) for arranging the words on the pages.

As

I understand it, I am being paid only for my work in arranging the

words; my property is that arrangement. The thoughts in this book, on

the contrary, are not mine. They came freely to me, and I give them

freely away. I have no "intellectual property," and I think

that all claimants to such property are thieves."

from

"The Joys of Sales Resistance" in What are People for?

The

plain fact is: I have accepted the gift of the ideas, copied

(borrowed, stolen?) the arrangement, and substituted the details to

fit my situation. Relatively few substitutions were needed, and that

was the point. Gradually, the structure and the words become more and

more my own. As with Wendell, the thoughts have come freely to me and

I expend considerable effort to share them. Some of the text became

part of an article published in the local newspaper. 3 I

might equally well have used Thoreau:

"AT

A CERTAIN season of our life we are accustomed to consider every spot

as the possible site of a house. I have thus surveyed the country on

every side within a dozen miles of where I live. In imagination I

have bought all the farms in succession, for all were to be bought,

and I knew their price. I walked over each farmer's premises, tasted

his wild apples, discoursed on husbandry with him, took his farm at

his price, at any price, mortgaging it to him in my mind; even put a

higher price on it- took everything but a deed of it- took his word

for his deed, for I dearly love to talk- cultivated it, and him too

to some extent, I trust, and withdrew when I had enjoyed it long

enough, leaving him to carry it on....Wherever I sat, there I might

live, and the landscape radiated from me accordingly....Well, there I

might live, I said; and there I did live, for an hour, a summer and a

winter life; saw how I could let the years run off, buffet the winter

through, and see the spring come in.

The future inhabitants of

this region, wherever they may place their houses, may be sure that

they have been anticipated....and then I let it lie, fallow,

perchance, for a man is rich in proportion to the number of things

which he can afford to let alone."

2.

1n 1995, the Millennium Forest stirred the enthusiasm of many people,

proposing to extend and improve native woodland areas all over

Scotland and re-establish and strengthen the connections between

communities and their local natural history. A local voluntary

association, Southwest Community Woodlands (SCW) formed, its core

being made up of folk whose interests in local environmental matters

had come together earlier in response to proposals to bury nuclear

waste in the granite hills at the heart of the Galloway Forest Park,

the bulk of which lies in the west of the Stewartry. Reforesting

Scotland, which developed from Bernard Planterose's "Tree

Planter's Guide to the Galaxy", also continues to be very

influential for a number of us. Southwest Community Woodlands Trust

(SCWT) was formed to provide the corporate identity required by

funding bodies, most notably the Millennium Forest for Scotland Trust

(MFST).

|

|

A divergence

of priorities

between MFST, (countable trees and hectares) and SCWT (people,

plants, creatures, places and their relationships) resulted in a

cordial(?) separation, and SCWT continues to develop in

association with a number of local initiatives, including

riparian planting along the upper Urr and elsewhere, native tree

nurseries, and the creation of a community woodland centre at

Taliesin.

|

3. See

Appendix

4.

tornat.html

5.

http://www.orionsociety.org/bookstore.html

Further

material on the ongoing relationship between self, soul and community

may be found at

credo.html

Return to North Glen

or Reading List

or Credo